2048 in OCaml

A New Flappy Bird

Have you ever heard about a game called 2048? There are discussions about it everywhere recently, be it on Stack Overflow, hacker news, reddit, twitter, facebook, you name it. It even got its own wikipedia entry.

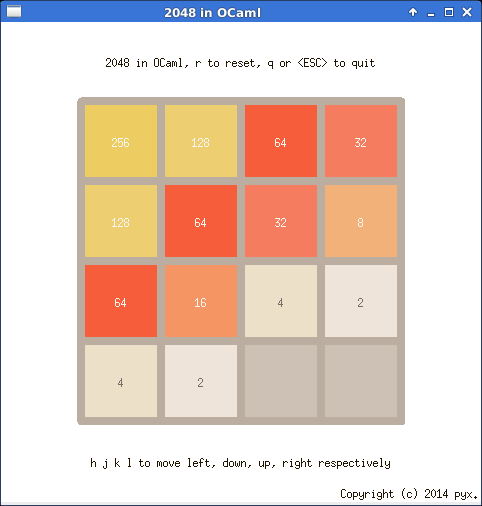

The gameplay is simple, you have a 4 x 4 grid with numbers, you can move all tiles in four directions, while moving, a couple adjacent tiles with same number will collide and be merged into a new tile with the number of their values added up, a new tile with number 2 or 4 will also appear randomly after each move, your goal is to come up with a tile with value 2048 (hence the name) before the game board is too crowded for new tile, in which case, you lose the game.

If you haven't already, please try to play it a few times, it's quite straightforward and fun to play, yet challenging and somewhat addictive. You will not regret, or you will, for it's such a time sink.

NIH Syndrome, anybody?

Do you know what's more fun to do? Dogfooding, that's correct, write your own version of 2048, because that's fun and doable in a few hours. This is why all the cool kids in town were busy reimplementing 2048 using their favorite programming languages lately.

In just a few days, I have seen many implementations and variants, in varying languages and technologies: javascript (same as the original one), C, C++, java, C#, python, ruby, Objective-C, haskell, etc., and the number keeps growing.

It seems like this thing is becoming the new Hello world, just like "roll-your-own-static-website-generator" was last year, and "write-your-own-dynamic-blog-engine-with-a-framework" a few years before that.

What I found interesting is, the game can make good use of monad, each game move can be implemented as monadic function and be chained, composed, transformed as such. So, with that pattern, I wrote my own version of 2048, in OCaml.

Monadic WTF?

For one thing, monad yields beautiful code, for example, the following code snippet from my version shows how to initialize a game board and then place two tiles randomly to begin with:

let init x y = Random.self_init (); let board = Board.init x y in let open Infix in playing board >>= spawn >>= spawn

Notice how I implemented this action "placing a new tile randomly", as a

monadic function (spawn) and how actions are chained with bind

operator (>>=), magnificent, isn't it?.

You don't have to be able to read OCaml to agree.

The following shows how to handle move:

let move m game = let open Infix in let action = match m with | Up -> Board.move_up | Down -> Board.move_down | Left -> Board.move_left | Right -> Board.move_right in Monad.lift action game >>= spawn

See how we combine "making a move" (Monad.lift action game) with

"placing a new tile" (spawn) then "checking for game winning/losing

condition" (check) automatically by bind function, as follows:

let bind game action = match game with | Playing, board -> begin match action board with | Playing, board' -> check board' | game -> game end | game -> game let ( >>= ) = Monad.bind

As you can see, the bind function is smart enough to stop taking moves when the game has finished. That is, if we are trying to play an action on a finished game, nothing will happen but passing the game object through the chain as it is, without explicit testing in each action function. Talk about avoiding boilerplate code again.

Hint

More specifically, the game-board object is modelled as a Writer Monad, tuple of (grid, step-count, score), while the game object is modelled as something similar to the Maybe Monad, tuple of (game-state, game-board). Each game action takes a game-board and yields, as after the action taken, the game-board in which contains updated step-count and score. The bind function takes responsibility for chaining game actions in turn, accumulating step-count and score, and updating game-state afterward. By freeing from these burden, we can have cleaner, less repetitive code in action functions.

Language support of automatic currying and infix operator defining make the above pattern possible. This is why I chose an ML family language (OCaml) for this project. Why not haskell then, you asked? As much as I love haskell, I picked OCaml because there are at least two implementations in haskell as of today already, besides, OCaml comes with cross-platform graphics library, so without external dependency, making a GUI is possible, here is how it looks:

2048 screenshot

Have time to spare? Get the source from Bitbucket or Github, and have fun.